About the Humanitarian Observatories

Can you tell me something about the Humanitarian observatories?

The concept of humanitarian observatories originated from the Humanitarian Governance Project, funded by the European Research Council and led by Thea Hilhorst. The idea emerged to analyze and validate the findings of the research, by drawing from the knowledge and experience of local actors.

Initially, the project focused on three countries: Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Colombia, and Ethiopia. As the project evolved, discussions surrounding the observatories expanded. Partners outside the initial research project expressed interest in organising their own observatories as well. At this point, the project transitioned from a research-driven initiative into a locally-based movement.

Over time, the Humanitarian Observatories developed into a knowledge and advocacy network that is not only country-based but also globally connected. The observatories reflect a diverse array of processes and experiences, serving as both a platform for sharing insights and advocating for changes in humanitarian practices and governance.

What was the idea behind the observatories?

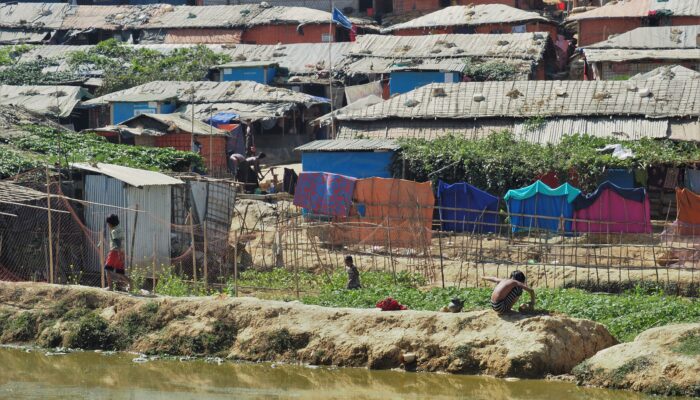

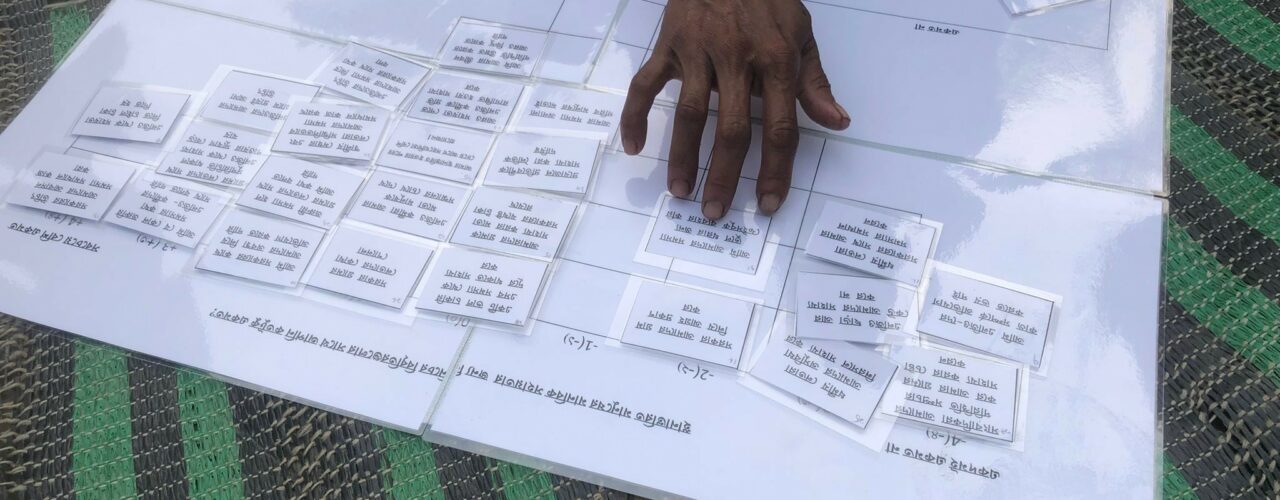

The humanitarian observatories emerged from a growing recognition that the international humanitarian system faces significant challenges, and that there is increasing attention on the role of local actors in humanitarian action. While many discussions about humanitarian response have traditionally taken place at the global level, there has been a shift toward emphasising the importance of local knowledge and the contributions of those who are directly involved in crises. The central idea behind the observatories is to highlight the grounded, embodied knowledge of those who are actively working in local contexts and humanitarian crises. This knowledge comes from individuals and organisations who experience these challenges firsthand and have a deep understanding of the realities on the ground. This opens opportunities to advocate for reforms within their own contexts. Moreover, by giving these local actors a platform, the observatories network aims to bring their insights into global discussions and shape the future of humanitarian response. For instance, the network is currently engaged in a number of global initiatives and studies where individual observatories are given an avenue to impart their perspectives on the effectiveness of humanitarian response as well as share their visions for the future of aid.

In other words, the observatories serve as a way to ensure that local perspectives are central to the debates on humanitarian action, and that the knowledge of those closest to the crises contributes to shaping policy and practice.

The central idea behind the observatories is to highlight the grounded, embodied knowledge of those who are actively working in local contexts and humanitarian crises. This knowledge comes from individuals and organisations who experience these challenges firsthand and have a deep understanding of the realities on the ground.

So is it true that the networks have their own network?

Exactly! The humanitarian observatories are flexible in their structure, and each one adapts to its local context and existing networks. In Latin America (based in Colombia), the observatory being hosted by a university means that the university takes on the responsibility of organising and coordinating the network. This typically involves bringing together a variety of actors, such as media outlets and civil society organisations, to form a comprehensive network. In the Philippines the observatory is hosted by an NGO, which already has its own established network and programs in place. In this case, the NGO’s existing relationships and initiatives naturally aligned with the goals of the observatory, and so their program essentially became a type of network for the observatory.

The key point here is that there is not one formula for organising the observatories. They evolve and grow in different ways based on the host organisation’s context, whether it’s academic institutions, NGOs, or other local actors. This adaptability helps the observatories thrive in various settings, making them both locally grounded and globally connected.

This adaptability helps the observatories thrive in various settings, making them both locally grounded and globally connected.

How are you still able to keep in touch with all of the observatories?

With 12 observatories currently in operation and more potentially joining, maintaining strong connections is crucial but can be challenging. These observatories are located in Ethiopia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Colombia (for Latin America), India (for South Asia), the Philippines, Namibia, Poland (for Central/Eastern Europe), Libya, Pakistan, Somalia, Nigeria, and the Netherlands. The Hague Humanitarian Studies Centre (HSC) plays a key role in coordinating and maintaining these links. To stay connected, the HSC checks in with the observatories every two to three months. These check-ins allow the HSC to understand how each observatory is progressing, what challenges they are facing, and what they might need.

In addition, the HSC organises an inter-observatory meeting twice a year. During these meetings, representatives from each observatory come together to discuss their activities, the issues they are encountering, and the possibility of launching collaborative projects. This fosters a sense of community and encourages cross-observatory collaboration, ensuring that the network remains dynamic and responsive. While the HSC plays a coordinative role, the network itself grows organically. The observatories are allowed to develop in their own directions, reflecting the unique contexts and needs of the countries in which they operate. This organic growth, while challenging to coordinate, allows the observatories to stay flexible and responsive to local changes and needs.

The HSC is still learning how to facilitate this evolving network. By embracing both structure and flexibility, they help maintain connections while allowing each observatory the space to develop its own identity and respond to its unique challenges.

What do the observatories want?

The observatories have diverse needs and desires, depending on their level of experience and the specific contexts in which they operate. Some observatories are more experienced in advocacy work, while others have less experience in this area and would like to build those skills. There’s a shared desire for more knowledge exchange between observatories, as some have valuable insights and experiences that could be beneficial to others. Additionally, there are instances where observatories have come together to explore common interests, facilitating collaboration and mutual learning. Recently, the network received an ERC proof of concept grant, which is designed to support the development of innovative ideas. The grant focuses on enhancing the network itself, providing more resources to improve coordination and open up collaborative opportunities among the observatories. This additional funding will help strengthen the connections between the observatories, allowing them to explore new avenues for collaboration, share insights more effectively, and further support each other in their humanitarian work. With these resources, the network is poised to grow even stronger, creating more opportunities for shared learning and collective action.

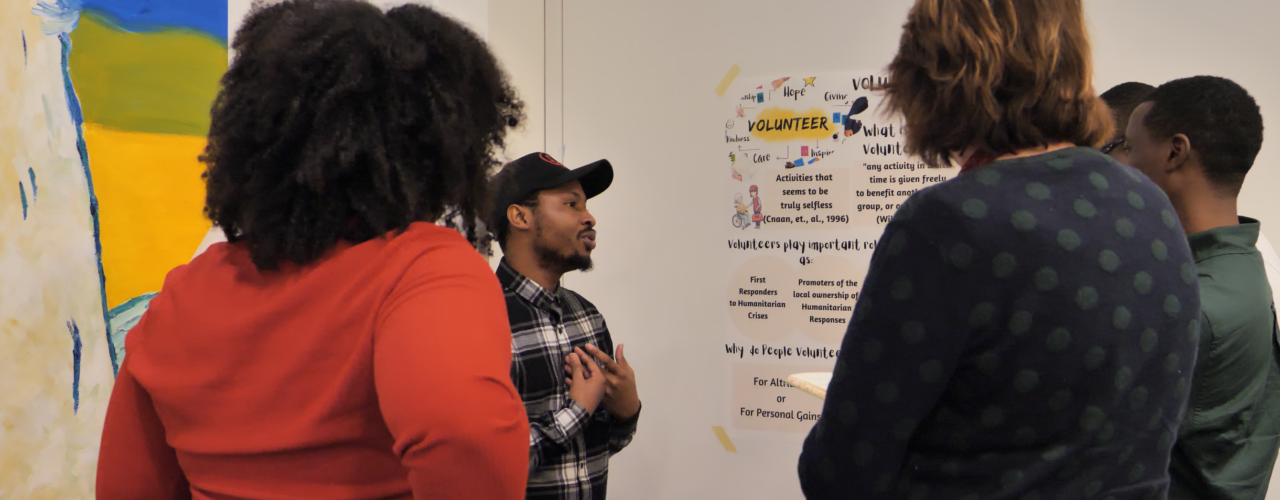

What do humanitarian observatories do on a daily basis?

Humanitarian observatories are self-governing and have the freedom to set their own agendas, which gives them the autonomy to decide what issues to focus on and what discussions to pursue. While this level of autonomy can sometimes feel uncomfortable for those who prefer more control over processes, it was a deliberate choice to empower the observatories and allow them to drive their own priorities based on the local contexts and needs they are addressing.

On a regular basis, the observatories meet to identify key issues and concerns related to the humanitarian context they are working within. These meetings provide a platform for discussing pressing challenges, and from these discussions, they develop action points and plans for addressing those issues.

For example, in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), one of the first issues the observatory focused on was sexual exploitation and abuse in the humanitarian sector. In response, they conducted a fact-finding mission and produced a report, which was later published as an article. They also organised an advocacy café, inviting different actors and government officials to participate in the conversation. One of the key points they examined was the role of village chiefs in making flood response efforts more effective.

In contrast, the Philippine observatory focuses more on disaster response and related issues, reflecting the local context and the particular challenges they face. They are also very active in campaigns for locally led humanitarian action. Emphasizing the ‘shift of power’ to communities affected by crisis, the observatory is trailblazing some initiatives, such as their advancement of community philanthropy.

Each observatory tailors its focus to the specific humanitarian issues affecting its region, and the autonomy they have in setting agendas allows them to address the most relevant and urgent matters in their local environments.

Each observatory tailors its focus to the specific humanitarian issues affecting its region, and the autonomy they have in setting agendas allows them to address the most relevant and urgent matters in their local environments.

Do the observatories find you or do you look for them?

As said before, the establishment of the first three humanitarian observatories was very intentional. The project was actively seeking out specific regions and partners to create the observatories. However, over time, the process evolved more organically. As the network grew, some organisations approached us, expressing a desire to be part of the network. For example, upon hearing of the network, an academic institution in Pakistan initiated their own observatory, mobilising their own resources to organise themselves, and then reached out to us to be part of the broader network.

Are there challenges within the project?

Yes, there are definitely challenges that come with facilitating and supporting the growth of the humanitarian observatories. One of the biggest challenges is finding an effective way to coordinate the growing network, especially considering practical issues like time zone differences. With observatories spread across different regions, organising inter-observatory meetings becomes difficult, as finding a suitable time that works for everyone can be a logistical challenge.

Another significant challenge is sustainability. While the observatories receive some initial support from the HSC to help them get started, the funding is limited. The question of what happens when the initial funds run out is a major concern. The sustainability of the observatories is crucial for their continued success, and the team is actively working on co-developing long-term funding strategies and plans to ensure that the observatories can continue to operate and grow independently over time. This is one of the key objectives we aim to accomplish through the ERC proof of concept grant.

How do you think the observatories can be more sustainable?

It’s not just about securing funding; it’s also about ensuring the observatories are recognised as legitimate players within the humanitarian network. Gaining this recognition is crucial for their sustainability, as it highlights the value they bring to the table. When the observatories are acknowledged for their knowledge and insights, they become integral to shaping humanitarian action and securing long-term support and collaboration. This recognition is a key factor in helping them thrive and continue making an impact. Second, it is important to develop a partnership model that is truly equitable. Many groups and networks fall apart when engagement becomes transactional. We are working hard to nurture a relationship that is based on trust, respect, and mutual support. Developing these relationships is essential to producing impactful collaborations.

It’s not just about securing funding; it’s also about ensuring the observatories are recognised as legitimate players within the humanitarian network.

How can the sector use the humanitarian observatories?

The humanitarian sector can work with the observatories by engaging with their knowledge and insights. The observatories offer unique, local perspectives that can help improve the accountability and effectiveness of humanitarian aid. By supporting these networks, alternatives to current approaches can be promoted, especially in areas where the sector still struggles, such as transparency and accountability. This could, however ambitious it may seem, help reshape the future of humanitarian aid.

The observatories offer unique, local perspectives that can help improve the accountability and effectiveness of humanitarian aid.

Why do you think it is good that KUNO recently became an observatory?

KUNO already plays a crucial role as a knowledge platform, with its broad reach and ability to bring together various stakeholders in the humanitarian field, especially in Europe which is also affected by humanitarian and human rights crises.

KUNO is very well-positioned to serve as a central hub for connecting these different networks and actors, fostering a more inclusive and global dialogue around humanitarian issues.

What is your dream with the observatories?

I would love to see the network flourish on its own. The goal is for the networks to be recognised for the value they bring and for their knowledge to be acknowledged. This would help counter the practices often seen in how humanitarian knowledge is created, where local expertise is taken without recognition. By highlighting and respecting the contributions of these networks, we can create a more inclusive and equitable approach to humanitarian action. The observatories are creating a space for that shift to happen—inviting others to engage with different forms of knowledge and firsthand experiences from the ground.

They offer a unique opportunity to immerse in the realities of humanitarian work as seen through the eyes of those living and working in these contexts. By engaging with the observatories, others can learn from this embodied knowledge, helping to break down barriers and redefine how humanitarian responses are shaped moving forward. It’s a powerful invitation to rethink the way we approach humanitarian action, making it more inclusive and contextually informed.

Read more about the observatories here.

On bliss you can read the blogs that different observatories wrote.

Date: 19th of February 2025

Author: Marianne van Elst-Sijtsma

Interviews with Observatories

Read the interview with the observatory in India here.

The Humanitarian Observatories are part of the ‘Humanitarian Observatories: Building a Knowledge and Advocacy Network on Humanitarian Governance’ project from February 2025-July 2026. This project has received funding from the European Union under the Horizon ERC Proof of Concept.

Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or European Research Council Executive Agency (ERCEA). Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.